I looked at the list of words on the green chalkboard. For the past ten minutes, the sweet Ghanaian pupils of this Volta Region school had been raising their hands to share the words in their donated independent reading books that they did not understand.

Here were a few of those words:

– Weirdest

– Garbage

– Massachusetts

– Mallow-blaster cookie

– Scarecrow

– Arnold

I was mystified. These children in the Total Child School’s Reading Club were between the ages of ten to sixteen, but despite their youth I had seen their stunningly advanced vocabulary in the Grand Quiz academic competition. With ease, these little academic powerhouses had won second place over all the other schools, rattling off words like: “physique,” “delusion,” “magistrate” and more.

So why were these superstar students having trouble with words that seemed so easy to my eyes?

I taught a brief lesson on context clues: inferring the meaning of difficult words through the context of the surrounding sentence, story, and illustrations, and then we set off to try the strategy together.

“Then Ms. Frizzle said the weirdest thing ever,” read tiny Abigail from her Magic Schoolbus book. “She said that we should get off the bus, even though it was flying in mid-air!”

“Thank you Abigail,” I said. “Looking at the context,” I asked the class, “what simple word could replace the one that is confusing us: “weirdest”?”

Several hands went up and I called on one. “Strangest!” the little voice sang out.

“Exactly!” I exclaimed, bounding to the board and writing: “Weirdest = Strangest.” As the Total Child pupils furiously scribbled notes into their notebooks, I turned around to my Ghanaian coworker John, and hissed, “Do you all really not use the word “weird” in Ghana? It’s an incredibly common word in America!”

John shook his head and smiled. “We use “strange,”” he explained. “These students have not heard the word “weird.”“

What a learning moment for me as a teacher! Ghana may be officially English-speaking, but Ghanaian vocabulary is a fascinating mix of advanced British English, indigenous-language influence, and language evolution over time. The result is a vocabulary set that is unique to Ghana.

The lesson went on in the same manner, practicing inferring difficult words through context clues, while simultaneously educating me on the common American words which Ghanaian students simply do not know.

The board began to look like this:

– Garbage = Rubbish

– Massachusetts = a region of America like Ghana’s Volta region. (The home of Madame Lillie and also of your penpals!)

– Cookie = Biscuit

– Scarecrow = a large doll to scare birds, like our parents use to guard their cassava crops

– Arnold = A common boy’s name in America and Britain

“You need to always remember,” I tell my Ghanaian students each time we set off writing our international penpal letters, “that things that are easy and obvious and everyday for you are completely unknown to your friends across the ocean. This means you must explain everything in excellent detail, so that your penpals will known what you are referring to.”

As an example, I told them that when I arrived in Ghana I had no idea what fufu was, and had never tried it in my life.

This statement always brings a roar of laughter from the kids, and at least ten exclamations of, “WHAT?!” Fufu is one of the most common and famous foods of Ghana, and not having heard of it is akin to entering America and saying you had never heard of, well (glancing at the board)… cookies!

For teachers (and in fact for everyone of all walks of life), there is the tendency to declare someone unintelligent or foolish if they don’t know a “simple” or “everyday” word or concept, especially if that student grew up in an ostensibly English-speaking country.

The lesson for me this week, however, was that we don’t realize the extent of what we don’t know, nor can we comprehend the vastness of the difference in our worldwide experiences.

Another example: because the names of the American students in the Ghana Penpal Exchange Project are of African-American, Latin-American, or European-American origin, many of my Ghanaian students have been confused about whether their penpal is a boy or a girl! American students assume that their name is familiar in Ghana and that they don’t need to clarify their gender, but in fact they do. Indeed, the same goes for Ghanaian students and their “Elikem,” “Easteria,” “Bless,” and “Praise” names!

What is “everyday” in one country is often “never” in another. What is “garbage” in one country may be “rubbish” in another. Knowing one set of vocabulary and not another doesn’t make us stupid! It just means that we need kind and thorough teachers, and eager and open minds to begin to acquire the words of other parts of the world.

Given that most of the donated books for this five-school Reading Club project are written by American or British authors, and given that I am an American teacher living in Ghana for three months, both the Ghanaian students and myself will learn a whole lot of new words and concepts between now and April!

Now the task will be to keep this open and inquiring spirit for the remainder of the year and beyond, and to encourage the rest of the teachers, students, and citizens of the world to consider adopting it as well!

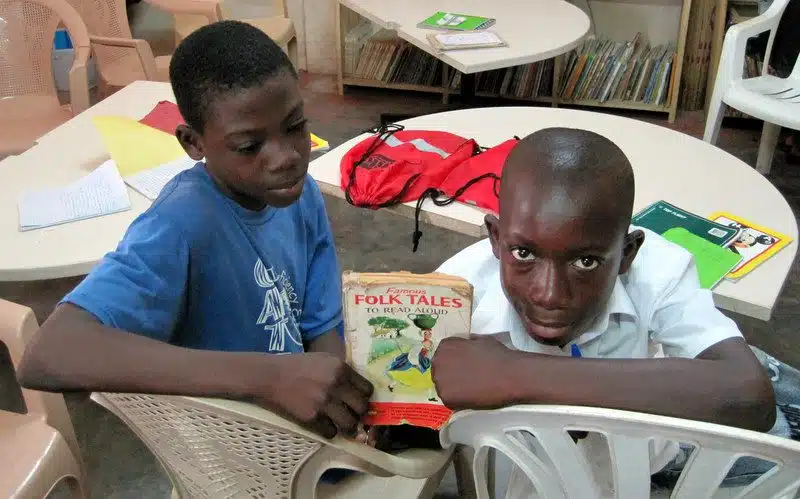

(Note: The first photo of this article is an inside view of Total Child School, where this tale took place. The other photos, however, come from teaching Cross-Culture class in the sun-dappled outdoors, and then running Reading Club class in the YCC office and library for the Youth Creating Change students.)

The author, Lillie Marshall, is a 6-foot-tall National Board Certified Teacher of English, fitness fan, and mother of two who has been a public school educator since 2003. She launched Around the World “L” Travel and Life Blog in 2009, and over 4.2 million readers have now visited this site. Lillie also runs TeachingTraveling.com and DrawingsOf.com. Subscribe to her monthly newsletter, and follow @WorldLillie on social media!

Tyson

Tuesday 17th of November 2015

Seeing these small cultural and language differences are definitely cool, and I'd even go as far as saying "weird." Never would I have imagined people knowing the kind of words like "physique" and "delusion", and then stopping to explain words such as weird or strange.

Ivanna C.

Monday 16th of November 2015

I agree that we have to keep an open mind to cultures all around us. We can't just assume that all around the world people do the same things we do. That is why when we talk with people from different places we have to be patient in explaining things, or be able to keep an open mind when we travel to other places. I really enjoyed this article!

Whitney

Wednesday 25th of February 2015

Honestly, I thought they would speak just like us, but to mix some advanced British English is impressive. This also proves how we need to expand our knowledge on different languages and how they may sound. What's common to them may be strange to us and deja vu. I'm also curious on what other words may be unknown to them and the types of words that are unknown to us. I hope you continue posting fascinating facts about the common language and much more about Ghana.

Runaway Brit

Friday 13th of April 2012

Great post! I came across this all the time when I worked in Vietnam, mainly due to British/American English differences. I was trying to teach the Keats' poem 'To Autumn' but my students had never heard of 'autumn' before, only 'fall' - of course, none of them mentioned this until right at the end of the lesson when one raised their hand and said "It's a lovely poem, but what is Autumn?!' I also once lost 15 students in the rainforest during an expedition when I had told them to turn left at the tarmac road. Not knowing what 'Tarmac' means, they all just wandered on into the forest!! That really taught me never to take prior knowledge for granted!

Confusion also occurs when they encounter a word denoting something they have never seen. I asked a class what was symbolic about the name Snowball for the character in Animal Farm (expecting comments like "it looks hard but falls apart when it hits a solid object") but they remained mute - surprising because they were usually such an animated and intelligent class - I then realised that none of them had ever seen snow!!

It is very enlightening to teach overseas!

Lillie

Friday 13th of April 2012

What perfect examples!!!

Drew

Sunday 18th of July 2010

Ooh! Ooh! Can I try?

want (US) = fancy (UK) Chips (US) = Crisps (UK) bathroom (US) = Dunny (AUS) = Loo (UK) Elevator (US) = Lift (UK) Apartment (US) = Flat (UK) drinking fountain (Western US) = bubbler (eastern US) pop (west US) = soda (midwest US) = coke (southern US) thing (most of the US) = deal (southern US)............as in "I'm not sure how this deal works (pointing at a computer or something confusing)."

Yes, even within our own country, some words, meanings, and accents can be different. Having southerners in half of my family and Californians in the other half made me aware at a very young age. World travel does, too.

This is a great exercise!