As the half-broken taxi thumped into another rocky crater on the endless dirt road in rural Ghana, I gasped to Collins, “You seriously bicycle forty-five minutes down this to work each morning?”

My friend chuckled and nodded.

After weeks of planning, I was finally going to see the remote school where my Ghanaian YCC colleague had been posted since September!

At four-thirty am, we hopped the first tro tro the two hours from Sogakope to Accra, then walked a winding mile to switch to another tro tro north for an hour and a half.

At the next town we squished into a shared taxi to travel an hour to the town in which Collins sleeps (as it is the last stop for electric power near his school), then switched to a fourth vehicle to brave the half-hour pockmarked path to Apau-Wawase School.

The journey took over five hours.

When I first met Collins in January, the twenty-nine year old YCC staff member explained that he had just finished his two-year teaching degree.

This meant, like all new Ghanaian teachers, that he had been posted to a random school within a chosen geographical region.

“Are you really saying that a Ghanaian teacher cannot select the town he will be posted to for the first two years of his teaching career?!” I asked, aghast and bratty from the pampering provided by my Boston Teachers Union.

“By all means, no,” said Collins. “And they will certainly always post you to the most remote or deprived school in the region.”

Thus, Collins and a handful of other fresh young teachers have been stationed in electricity-free, vibrantly green, far-as-heck Apau-Wawase Primary and Junior High School.

We alighted from the broken-windshield taxi (which we later saw sputter and break down on a dirt crater down the road), and headed down the serene green field towards the school.

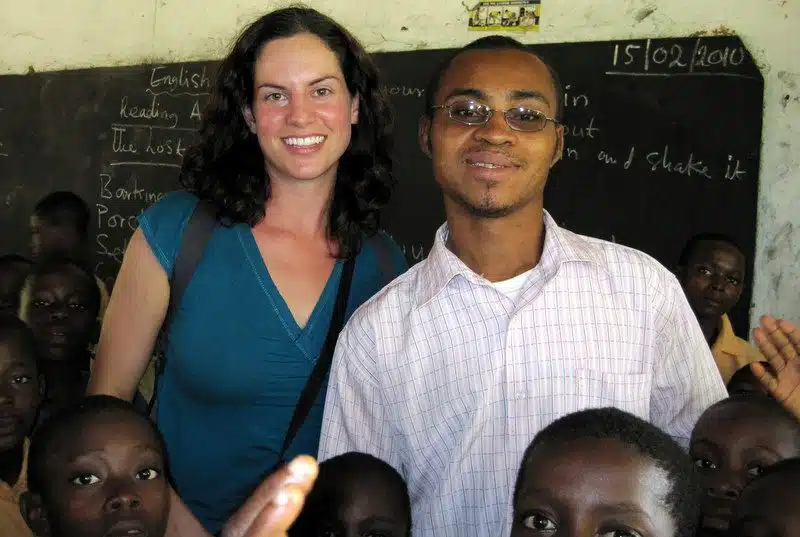

Oh, Ghanaian hospitality! We strode past the classrooms (“Obroni!!!” gasped the kids, gaping at my white skin) and right to the headmaster, who welcomed me heartily and pulled out chairs so we could sit and chat under the shade of a lush tree.

I explained that I am a teacher from America and was fascinated to visit my friend’s school.

The jolly headmaster then arranged for me to visit every single classroom in the school.

We entered the kindergarten first, which had roughly seventy students squished onto wooden benches. The headmaster introduced me in Twi, and I waved and said a garbled Twi, “Thank You!”

Then Collins led the students in a rousing song replete with clapping and arm dancing. Very, very cute!

In Form (Grade) One, the headmaster asked the children in Twi: “Have you ever seen a white person in your village before?”

“NO, NEVER!!!” hollered the children in unison.

Collins, who is freakishly light-skinned for a Ghanaian and is always being made fun of for it, exclaimed, “You call ME obroni, but now you see someone even lighter!” Uproarious laughter ensued.

After visiting Form Six, the headmaster directed us to walk the mile to the Junior High School and told Collins that he, himself, would teach my friend’s class so that Collins could accompany me. How kind!

We were sweaty by the time we arrived at the JHS, and I thought again of Collins’s forty-five minute bicycle commute in this blazing Ghanaian sun!

“You are welcome,” sang Collins’s young colleagues, giving us the classic handshake-plus-middle-finger-snap greeting.

“The students are on their free period,” said teacher David, “and we don’t mess with their free period. So come take a seat under the shade here until it’s time to go in.”

I thanked them and gazed over at the students chatting calmly in the classrooms.

“You know,” I mused, “In our school in Boston we could never have a free period like this for fear that fights and destruction would result. Even our lunch time is just about fifteen minutes long, and students are not allowed to stand up, else they start rioting!”

The young teachers shook their heads. “Here,” Samuel said, “we Ghanaians love discipline. We use the cane and we expect respect. I think it would be very difficult for us to teach in America! Students there are so… free.”

“Sometimes too free,” I muttered, remembering the screaming swears, fistfights, and electronics under the table. As an American teacher, I have much to learn from the high behavioral standards of Ghana’s educators!

The free period ended and all the Junior High School students were assembled into one room.

“Madame Lillie is a teacher visiting from America,” said Collins in his introduction, “and she does not speak much Ewe or Twi, so we will all talk in English. Those of you who speak more English than others, please help to translate for your friends!”

“I am here to talk to you about the true importance of education in your lives,” I began, launching into my mini-speech.

It was great to hear the students mutter, “YES!” or “Amen!” after different phrases. I love this classic African audience-interaction style. It makes a speaker feel heard!

“Now,” I concluded, “in preparation for the article I will write about this wonderful visit, could you please raise your hands and tell me more about your school and your lives?“

Students were painfully shy, but hands slowly began to go up.

“What is positive,” said one girl, “is that we have good teachers here to help us learn.” The children nodded in gratitude towards the young men in front of them, and the teachers smiled.

“What is difficult,” said one boy, “is we have no computers.”

Wild laughter filled the classroom. “We have no ELECTRICITY!” one girl roared. “We do not even have light at night to study!” Murmurs of agreement resounded.

“What is positive,” said one boy, “is our community grows many crops to eat.”

“What is difficult, however,” added another, “is that the road is in such poor condition and transportation is so expensive, that often we cannot get our foodstuffs to market to sell. This means our crops rot, and we lose money.”

“Most of us have never been beyond the next village,” a girl added shyly.

“One way to see more of the world,” Collins said, “is to read. However, we have no books beyond the state textbooks, and no one has reading material at home.”

“But the fundamental problem,” a brave boy stated, standing, “is that many of us CANNOT read.”

Children started to giggle, but Collins loudly shushed them. “HE HAS SPOKEN THE TRUTH,” Collins gravely boomed.

Students looked left and right, sighed, then said: “It is true.”

Collins turned to me. “Even though many of our students are nearly adults, they are having so much difficulty with reading. Part of the problem is that they have no educational materials in their homes, but perhaps an even bigger part is that they have no one at home who will support their efforts to learn.”

Collins turned towards the class. “Who here,” he asked, “is basically raising themselves because his or her parents are not around or not assisting financially, mentally, or emotionally?”

Nearly half of the hands in the class went up.

“So many of these children really want to learn,” said Collins, turning to me, “but without any assistance from the adults in their lives, how can they pay for the uniform, shoes, and books required to attend school? If you look around, you will even see that some of the students right now are not wearing a uniform because they cannot afford it.”

After the meeting, we all stood outside in the sun, and a half dozen children began drifting towards us to tell their individual stories. They spoke rapidly in Ewe to Collins, and Collins translated for me.

“I was orphaned and now stay with someone who does not care for me,” explained Odoi Patricia. “I am forced to work farming cassava in the morning and afternoon, meaning I am often late for school, though I do not want to be.”

It was the same story for a boy who was made to tap palm wine by his guardian, though he receives no financial help for school in return.

Two shy twins explained a similar tale, and Collins explained, “With this stress, it makes learning so hard! Some girls are lured into prostitution if they become desperate, so we must try so hard to help them.”

Another boy explained of his serious heart condition which attacks every year and makes it impossible to breathe.

Through all of this, I couldn’t stop thinking about Boston. Would you believe me if I told you that many of these problems are shockingly similar across the ocean?

A heartbreaking number of students in Boston are also living with people who do not or will not give them the support needed to really learn.

Some don’t have a single book at home. Some must risk cruel teasing at school because they cannot afford adequate clothes. Many come to school starvingly hungry.

Like the students in Apau-Wawase, hundreds of Boston kids come to school late and exhausted because they are forced to work long hours at Best Buy or Old Navy or Dunkin’ Donuts to help support their families.

Like the Ghanaian student who explained the terror of his sickness, so many Boston students battle with Asthma, which sometimes attacks so ferociously that the child cannot even leave his or her house.

As Collins said: “With such awful difficulties to struggle with each day, it is very, very hard to focus on school and learning.”

So the question becomes: WHO do we choose to help, and HOW do we help? Do we send funds to the Haitian earthquake victims? Do we volunteer in Boston tutoring centers? Do we donate to Africa?

For myself, my answer is: I will try to do what I can everywhere. In the case of Apau-Wawase, I will try to get some donations of used children’s books and clothing for the village the next time Collins comes to Sogakope.

I will also write this article so that folks around the world can get the chance to see a school they had never before heard of.

However, as I sat quietly in the back of Collins’s Form Four classroom and watched the passion and energy with which he led his forty students through a reading lesson, I realized something: No matter how many books or shoes overseas donors may contribute to this worthy school, the most profound assistance to the village is being given each and every day by the hard-working headmaster and teachers of the Apau-Wawase Public School.

“Many people in Ghana do not respect teachers,” explained Collins’s colleague, David to me. On that day, David was suffering from a feverish bout of Malaria, but had still come to work.

David continued, “People see teaching as a job that Ghanaians turn to when they have been rejected from all other jobs.”

“So, then,” I asked the young teacher, feeling depressed, “What is the dream job you hope to have instead of teaching?”

David didn’t miss a beat. “I have always wanted to be a teacher,” he replied.

I smiled in admiration.

A huge THANK YOU to the students and staff of Apau-Wawase Primary and JHS School for making me feel so very welcome, and I wish them all so much strength and success in the phenomenal work they do each day!

The author, Lillie Marshall, is a 6-foot-tall National Board Certified Teacher of English, fitness fan, and mother of two who has been a public school educator since 2003. She launched Around the World “L” Travel and Life Blog in 2009, and over 4.2 million readers have now visited this site. Lillie also runs TeachingTraveling.com and DrawingsOf.com. Subscribe to her monthly newsletter, and follow @WorldLillie on social media!

Backpackingranny

Tuesday 23rd of July 2013

Kwabla is the founder of a new program called In The Queue, and I am in Ghana now to launch the program. We have selected 12 students to be the recipients of a donation toward their school fee, or to buy necessary school supplies. Two of the children from this village have been selected by their teacher, Collins. So yesterday I traveled here to present the students and their parents with 100 Ghana cedis each. It was an incredible experience and we talked admirably about Lillie all the way up that long windy and bumpy road to the village. The students who were selected are Isaac and Patricia. I'm not sure if it is the same Patricia who was mentioned in the article or not. Oh yes, Lillie, the journey to the village was just as you described. I'm thinking now that I should have re-read your article before setting off because by the time we got there the primary class had closed for the day. I was traveling with Bold Bernard my right hand man. I thought of traveling alone, but am so glad that he was with me. I also met Samuel. Thank you for paving the way Lillie!

Lillie

Tuesday 23rd of July 2013

So inspiring to hear these updates!!!! Please keep them coming, and feel admiration for the good work you are doing. Send my love to everyone in Ghana from me and our baby-to-be-born-in-4-months!

Drew

Sunday 18th of July 2010

Parents, SUPPORT YOUR CHILDREN, WHATEVER THE ENDEAVOR!!

When I coach wrestlers, I invite, and occasionally have to beg parents to come to matches to support their children. It means the world to them.

Through this post, we have a glaring example of what lack of parental support can mean to a society. We see it all over America as well.

I hope that the parents of the children at Apau-Wawase Primary and Junior High School will come around soon so as to prevent another tragedy.

Imported Blogger Comments

Friday 28th of May 2010

Aaron from Happytimeblog said... Since following along with your blog I'm completely inspired to try and get into something like this... If you have any advice on how to get into teaching English abroad I would blooming love it... I don't (but can have) a TEFL but I've heard that they're not really worth the paper... What would you suggest? I'm interested in the long term and short!

February 17, 2010 7:28 PM

Lillie M. said... Aaron,

Fabulous! Ooh, there are SO many ways to go about getting an English teaching gig.

I got certified in TEFL myself through a great month-long course in Costa Rica in which I learned a lot, so if you want more info on that email me. That said, I agree that much of the learning happens on the job, so your best bet may just be to shop around for a great place to volunteer or work.

There are sooo many schools and programs out there, so think about what you want and where you want to be and who you want to be with, and start asking around, both online and in person.

If you want to be paid, the process will be more formal, of course, but if you want to volunteer, what school or afterschool program wouldn't be delighted to have your cool self on board for a month or two?

Feel free to contact me with any more questions or specifics! And... yay!

- Lillie

February 17, 2010 8:10 PM

Chelsy Hooper said... Awesome article! Can't wait to share with my students. I'm sure they will want to send them books after they read this. They were so excited to read their student stories and send an email. And I understand your viewpoints- I taught in Philadelphia for a year and know exactly what you mean. Both types of students are deprived, just in different ways. Would love to hear more about how we can help.

February 17, 2010 9:45 PM

nodebtworldtravel.com said... So many things flow from education. More so, so many things flow being able to read. It's a fundamental part of being a functioning member of society, any society.

February 18, 2010 1:25 AM

Anonymous said... I never understand, why the Ghana government asks for school fees and uniform. The children are the future of Ghana, the parents are poor. Let them go to school!

February 18, 2010 1:35 AM

Luddy Sr. said... What a wonderful article Lil! Thanks for giving me a glimpse into Collins' school. He's doing such great work. I'm so proud of him.

I want to help as well....I have to raise some funds first, but as soon as I can I'll get involved!

February 18, 2010 4:31 AM

eli said... I'm so happy to see you off doing such enlightening traveling! Your adventure has evolved so meaningfully, so much more than backpacking!

February 18, 2010 7:33 AM

Lillie M. said... Utterly tragic to find out today that the girl standing alone in the ninth picture down has just fallen ill and passed away. May this remind us that Development Work is life or death, and we must not give up in our efforts!

April 3, 2010 5:19 PM