The Vietnam war slashed its knife through America. My parents marched in anti-war protests, sprinting from billy-club smashing police, and aching with frustration at the movement’s powerlessness to stop the conflict.

My father became a teacher to avoid being thrown into the bloody battle overseas; others were tragically drafted and deployed. Even today, new Vietnam War films, books, and stories emerge each month. The Vietnam war is deep within us as Americans.

And yet, if WE are so deeply impacted, all the way on the other side of the globe, how much more affected is Vietnam, where the bombs actually exploded?

From 1959 to 1975, the war slaughtered 58,159 U.S. soldiers, 1.5 to 2 million Laotians and Cambodians, and 3 to 4 million Vietnamese, according to the Vietnam War Archive. The Vietnam “War Remnants Museum” in Ho Chi Minh City is a brutal reminder of this.

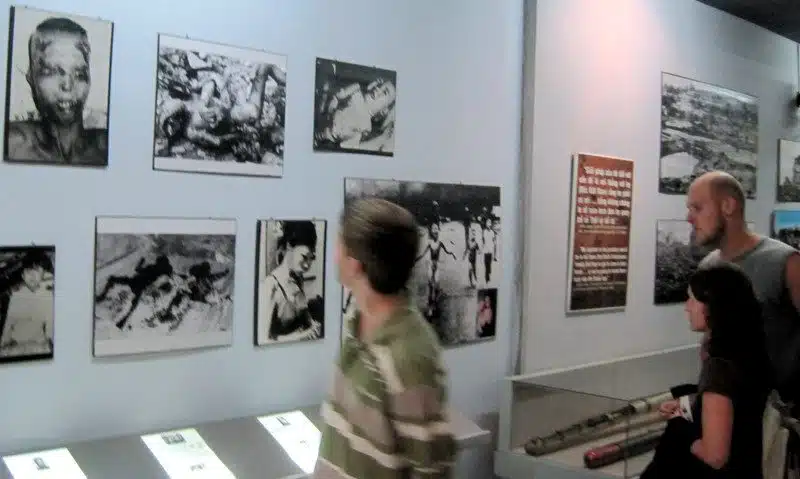

The museum was packed with Western and Asian tourists, but the halls were dead silent as visitors walked past the essays and haunting photos, each taking an emotional journey of their own. Which of these visitors actually served in the war, or experienced it from the Vietnamese side? For some, was this a personal pilgrimage to honor a family member?

Upstairs is a photo-filled timeline of the conflict. Particularly disturbing was the following plaque: “On August 1964, the U.S. Army fabricated a story about the so-called “Gulf of Tonkin Incident”, falsely accusing the Navy of Vietnam of having attacked the U.S destroyer Maddox.

This gave the U.S. Congress pretext for approving the “Gulf of Tonkin Resolution”, authorizing the U.S. president to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the United States.”

The echoes to the Iraq War and supposed “Weapons of Mass Destruction” are painful: lies leading to a senseless, brutal war.

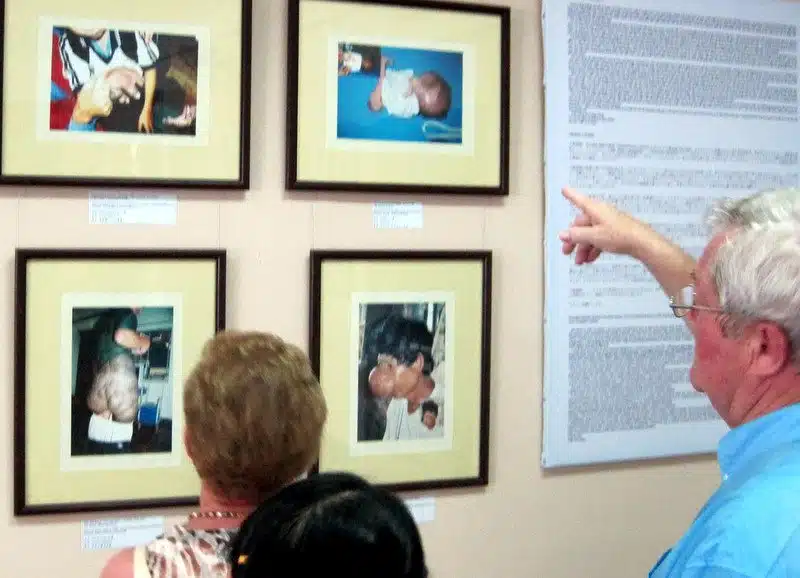

Downstairs in the museum are two galleries full of photos documenting the birth defects caused the 12 to 20 million gallons of Agent Orange the U.S. dumped upon Vietnam to kill the trees the “enemy” was hiding behind. The range of these deformities slap you; the museum even has a liquid tank which holds two and a half Agent Orange-mangled stillborn children.

Then comes the wall about the My Lai massacre. In this 1968 atrocity, U.S. troops murdered 347 to 504 unarmed citizens in South Vietnam, most of whom were women, children, and elders. The museum has printed giant color photos of the mutilated dead bodies of the victims, and lists their names and ages.

I left the museum nauseous, crying for the victims, and outraged at the criminal foolishness of the war. The fighter-plane-filled courtyard was silent.

I reached the gates, wondering how Vietnam could ever erase the scars.

…And then suddenly life exploded all around me.

“Motorbike, miss?” “Hat, miss?” “You want a postcard? T-Shirt? Scarf?” I grinned at the horde of salespeople around the gates and tourbuses, and said with all the love I could muster: “No thank you.” By that I meant: “Long live the undying spirit of humanity, of regrowth, of reaching and rising!”

Tao Dan Park was drenched in a thick mist which wove through the palm trees and magenta flowers. And there it was again: Life. A wedding! Thirty children doing aerobics in front of a sea serpent-shaped hedge! A woman holding her mother’s hand as they walked down the path! Fifteen girls gathered around photos glowing from a laptop! Life.

I shook my head in wonder at how a battle zone could rebuild one short generation later. How is that even possible?

And then I realized: to a lesser extent, all of us at Charlestown High School have been rebuilding a war zone.

In 1975 (exactly the same year the Vietnam War ended), Boston Public Schools were ordered to begin forced busing to racially integrate the schools. Charlestown High, a working class White Irish school, exploded in violence when the buses of Black students arrived.

White adults hurled rocks and swears, teachers and students barricaded themselves in upper floor classrooms, desperately calling for police aid, and White mobs physically assaulted Blacks, even dangling a young girl out a window. The stories told by Val Shelley, a CHS employee since desegregation, make you sick to your stomach. It was a bloody war zone.

And yet recently, when our class read the chapters of “All Souls” that deal with racial busing in Boston, my students were shocked. “This used to be a White school?” asked Derrick in disbelief, looking out across the thirty-one Black and Latino students (with one Asian and one White girl). White flight had struck right after busing. “No way,” he said.

Our class read on about the violence and racial battles on the streets right outside our classroom, only one short generation ago.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw Courtney slip her pale white hand into Lorenzo’s dark one. “I don’t hate you,” she whispered with a grin. He squeezed her hand with a smile and replied, “I know.”

The author, Lillie Marshall, is a 6-foot-tall National Board Certified Teacher of English, fitness fan, and mother of two who has been a public school educator since 2003. She launched Around the World “L” Travel and Life Blog in 2009, and over 4.2 million readers have now visited this site. Lillie also runs TeachingTraveling.com and DrawingsOf.com. Subscribe to her monthly newsletter, and follow @WorldLillie on social media!

EndsExpect

Wednesday 27th of April 2016

Your essay over simplifies a very complicated situation. Many people in South Vietnam fought and died against the North. Many of the Catholic Vietnamese directly joined in fighting alongside the US, because they knew the communists would persecute them!

To people like you... you just look at the war from an American perspective. Even when you try to see the Vietnamese point of view you do so in an ethnocentric way.

Had we never abandoned South Vietnam, it would be a wealthy country today like Japan or South Korea. Instead millions starved to death under communist stupidity until they followed China's lead and embraced capitalism. At the time of the war, most people believe the North under Ho Chi Minh were going to rule like the North Koreans... a brutal and inhumane dictatorship. Had we realized the Uncle Ho as the Vietnamese call him, was a patriot and a nationalist before anything else, the war would not have been necessary. However, hindsight is 20/20.

So, when you go through the south and look at war memorials. Remember that the people living there felt betrayed when we packed up and left. The communists stole everything they owned, imprisoned, and tortured their family. Those divisions are still VERY deeply felt within the country. I'm not chastising you or saying that you are wrong in what you say... only that I hope you break out of your ethnocentric bubble and meet Vietnamese people and talk to them about how they feel, not how your hippy parents feel.

Lillie

Wednesday 27th of April 2016

Very powerful and important points. Thank you for taking the time to write.

alicia

Tuesday 8th of July 2014

This is a wonderful, touching essay - thank-you!

Lillie

Tuesday 8th of July 2014

Thanks so much for reading and taking the time to comment!

Agness

Sunday 27th of October 2013

This post brings back great memories from Vietnam. I was there and remember this place very well. Sad and touching, but extremely interesting to explore.

James

Friday 15th of February 2013

Thanks for a wonderful article. Scary as it was, most Vietnamese are over the war. Museum, statue, memorial are there to remind us all of the nation's spirit and strong will during the time of crisis.

Lillie

Friday 15th of February 2013

Beautifully said. Thanks for reading!

Spencer Gao

Wednesday 13th of April 2011

I think that the agent orange thing was really terrible. It's almost equal to an atomic bobm because it kills all the plants and causes birth defects for a long time. The baby tank thing is really nasty.